Big thanks to Leila Ettachfini for this new article about Queer Trans War Ban! We are getting ready to create new sticker and poster designs for 2019 summer outreach, so if you have ideas or designs, be in touch!

These LGBTQ Activists Don’t Want Queer and Trans People Serving in the Military

While the trans military ban has spurred a flurry of media coverage in support of trans troops, these activists still believe the military has no respect for human rights.

By Leila Ettachfini

Earlier this year, The New York Times published a story headlined “Transgender Troops Caught Between a Welcoming Military and a Hostile Government.” The piece highlights the discrepancy between the way that three trans service members were welcomed into their squadrons and platoons and the hostility they’ve faced from the Trump Administration. Rather than focusing on the work that the main subject, Senior Airman Sterling Crutcher, does as part of a B-52 bomber squadron, the piece describes the community that he found in the military: “He relaxes on weekends by playing video games and has Airsoft gun battles with the other troops from his unit.”

That piece is just one in a wave of media coverage over the last two years focused on what has come to be known as the “trans military ban.” In July 2017, Donald Trump haphazardly announced his plans to ban transgender people from serving in the military. After federal judges across the country struck down his administration’s attempts to implement the policy over the following year and a half, the ban eventually went into effect, with help from the Supreme Court, in April 2019. Since Trump’s announcement, the trans military ban has remained the most prominent LGBTQ issue in the country, occupying significant space in liberal and conservative media coverage—the latter supporting the ban and the former opposing it.

Some LGBTQ activists on the left, however, believe that both sides are getting it wrong—and that liberal media, in particular, is pushing a dangerous narrative about trans military service.

“Since Trump’s trans ban, we’re seeing this ongoing, increasing coverage that glorifies trans military service and makes it out to be this wonderful opportunity for trans people in this dignified job,” says Dean Spade, a trans activist and law professor based in Seattle. “[It] completely hides the realities of people’s experiences in the military, as vets, and what the military does.”

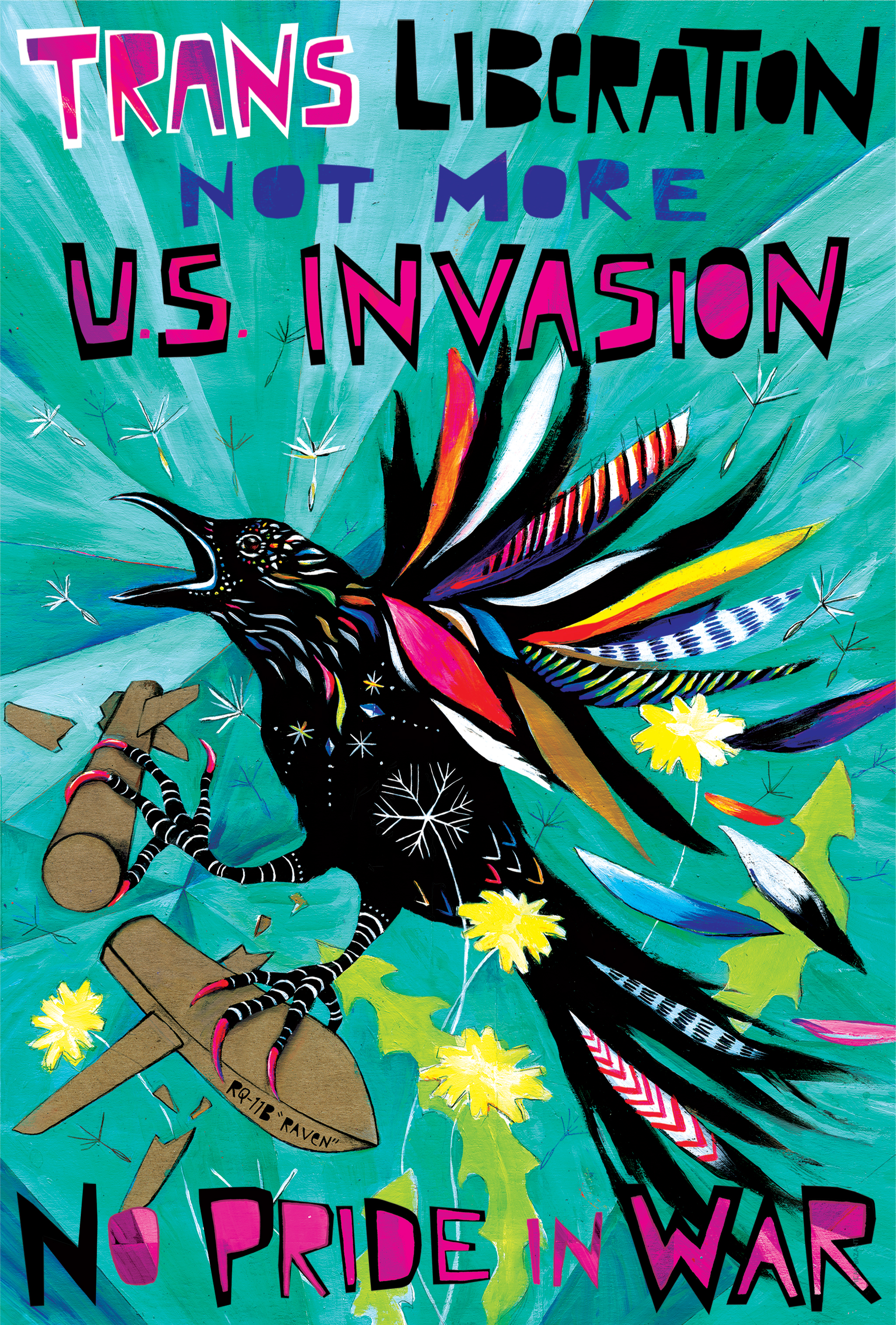

To push back against what they percieve as a wide-spread pro-military response to the ban, in 2017, Spade and a group of similarly-minded activists launched Queer Trans War Ban, a queer and trans anti-militarism campaign. The homepage of the campain’s website reads, “A bomb dropped by a queer or trans soldier still kills.” It also offers a toolkit for organizers to use to condemn military service within the LGBTQ community, including handouts, stickers, a T-shirt design, and a poster with the phrases “Trans liberation not more US invasion,” and “No pride in war.” The campaign lists a number of reasons for their anti-militarism stance, including the US military’s history of high civilian casualties, sexual violence, and immense contributions to global pollution.

The activists behind Queer Trans War Ban are not alone in their sentiments. For some activists, like Mirna Haidar, the issue hits close to home. Haidar is a law student and survivor of the Israeli-Lebanese conflict and the 2006 Lebanon War currently living in New York on asylum. Last year, Haidar took up anti-militarism activism on their campus at CUNY Law School after learning about the Soloman Amendment, a federal law that cuts funding to schools that prohibit military recruitment on campus.

“As a queer Muslim immigrant person who survived a war, the last thing I want is a queer person being the person launching the bomb at me and my family,” they said. “So, I started organizing and moving things around on campus, and a lot of people showed up.” Recently, during a military recruitment effort on campus, Haidar and other queer activists at CUNY set up a stand next to the recruitment booth where they displayed posters from Queer Trans War Ban alongside statistics about military violence and answered questions about anti-militarism.

Although Haidar is anti-military, they do not support Trump’s ban on trans people serving in the military. “I’m definitely against any discrimination based on someone being trans or queer, etc.,” they said. “But, I think doing trans-inclusive things within an oppressive system is a dangerous door to enter; dangerous [because] we’re misconstruing what the reality of the army is. We’re further traumatizing trans folks and queer folks and Muslim folks by entering those institutions.”

To many, the work of Queer Trans War Ban and other anti-militarism LGBTQ activists may seem radical—but it is by no means novel. Anti-militarism activism in direct response to military policy surrounding LGBTQ people took hold in the 1990s as the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell (DADT) policy was being considered, before it was eventually instituted by the Clinton Administration in 1994. In 1992, an outreach packet published in San Francisco called “We Like Our Queers Out of Uniform” outlined the history of “harassment, intimidation, violence and terror that the military inflicts on lesbian and gay service people.”

Leading up to the ending of DADT by the Obama Administration in 2011, anti-militarism activists again had reason to push their cause. “The capacity for increased carnage should not be celebrated as a victory,” wrote Cindy Sheehan, the mother of Specialist Casey A. Sheehan, a soldier killed in Iraq, in a 2010 op-ed for Al-Jazeera called “Don’t Go, Don’t Kill.”

Despite a history of queer anti-militarism activism, both Spade and Haidar have received support and criticism of their work from inside and outside the LGBTQ community.

Organizations like SPART*A, a transgender military advocacy organization, maintain that military service is often good for LGBTQ people. SPART*A president Blake Dremann told VICE, “For many LGBT folks, the military is a pipeline out of poverty, violent homes, homelessness, and hostile communities. It provides educational opportunities or the chance to learn a trade. Working on equality issues in the military does not harm civilian movements for equality; it provides greater options for trans persons.”

Still, he said, “We absolutely respect [anti-military LGBTQ people’s] First Amendment rights to speak their mind and advocate for non-military solutions and the choice of any individual in whether or not they feel the military is the right fit for them.”

To the point that the military can be beneficial to queer and trans people, something Spade and Haidar hear often, Spade argues that LGBTQ people should demand “actual economic justice instead of being cannon fodder for this horrible system.”

Haidar says that they’ve received pushback from some who say that anti-militarism is unsupportive of trans people under the context of the military ban. But, to Haidar, it’s about a “holistic agenda.”