Continue reading “The Ability to Live: What Trump’s Health Cuts Mean for People with Disabilities”

Interview about Drugs and Sex and Bathrooms

It was exciting to receive the new issue of Original Plumbing that includes an interview I mentioned before that has had me looking back at old zines and photos from the 1990’s and early 2000’s. Here is the text and some photos of how the editors laid it out in the magazine. Thanks to Amos and Rocco!

OP: Can you tell me what happened to you in Grand Central in 2002? DS: In February 2002, I attended the protest against the World Economic Forum meetings that were being held in New York City. It was a large anti-globalization protest, similar to the protests that had happened in 1999 in Seattle against the World Trade Organization, in Quebec City in 2001 against the proposed Free Trade Area of the Americas. These were all protests against summits where the rich and powerful gathered to plan economic policies that harm most people and the planet. It was also very shortly after the World Trade Center bombing on 9/11/01. The New York City government prepared for the protest by turning out the police in outrageous numbers. I participated in the protest with friends, and then we left. On our way home we decided to go to Grand Central Station to use the bathrooms because we had been out in the streets for hours and were in need. I went into the men’s a cop followed me, stopped me and asked for my ID. I explained that I was in the right place and I just needed to use the bathroom, and the cop started to arrest me. My friend Craig saw the cop follow me in and went in to see if I was okay. He and our friend Ananda who was nearby in the corridor both tried to intervene and advocate for me and they were arrested too. Others of our friend who were with us tried to get to us and were held back by a line of riot cops who showed up. We spent about 24 hours in jail. When we were transferred from the jail where we’d been to the cells at the court, a random court-appointed laywer came to talk to me about my arraignment. I had recently graduated law school but had never represented anyone in criminal court and didn’t really know what was going on or what was going to happen to me, or even whether or not I could actually be convicted of something. The lawyer who came to talk to me asked me about my genitals and when I told him I did not think it was relevant, he was mean and dismissive. It was really scary to see how even though, in so many ways, I was so privileged in this situation being a white person, employed, fancy-educated person, I felt really vulnerable in this system facing transphobia from the cops & the lawyer. Craig and I did an interview right after the arrest that is interesting to read because it shares what our take was on trans politics, the anti-globalization movement and bathrooms at the time.

OP: What kind of action came as a result of that incident? DS: The story of my arrest circulated as one of the news items about the protest. I got emails from people all over the country who had had similar experiences in bathrooms being falsely arrested or harassed, and also from people who had been beaten in bathrooms. There were also a lot of people in my local community in New York City who wanted to mobilize about what had happened. The connections I made and the information I gathered during this time about what was happening to trans people at the hands of the police and the inability of trans people to get effective legal help was important in building up to the founding of the Sylvia Rivera Law Project, which opened in Fall 2002. One of the first projects SRLP did was creating our 30 minute movie, Toilet Training and the activist/educator toolkit that goes with it. This movie was the first about this issue and has been used in all kinds of institutional settings by people trying to change bathroom access. It is still being used a lot, but it seems a bit dated now (finished in 2003) so we are in the process of making a new version with the brilliant trans artist and filmmaker who made the first version, Tara Mateik. Another influential thing, for me, about this experience that I think may be of interest to OP readers was that many trans people said negative things about me online after this arrest. Many people wrote that I must not pass and this must have been the cause of my arrest, so I was at fault for the arrest. It was a difficult moment of seeing the internalized transphobia in trans communities, and it felt like a betrayal. We made a zine, authored by “the Anti-Capitalist Tranny Brigade” as part of our organizing after the arrest called Piss and Vinegar. The title references the vinegar-soaked bandanas activists wore to the protest to protect against police teargas, as well as the phrase “full of piss and vinegar” meaning full of youthful energy, boisterous, rowdy. In the zine we wrote about how this policing within trans communities harms us all. It was very important to me in my work at SRLP and all my work going forward to try to build shared analysis in trans communities that rejects gender policing of all kinds, by cops and between trans people, and is committed to a vision of gender self-determination where no matter how a person looks, dresses, speaks or what medical care they seek, no one should be put in a cage.

OP: Had you considered yourself an activist before that all happened? DS: Yes, I was already a part of activist work in New York City. I had been part of multi-issue queer work going on in NYC when Giuliani was mayor that was focused pushing back against his administration’s brutal treatment of welfare recipients, its increased policing (especially of public parks and bars that were queer & trans gathering places), its attacks on sex workers and immigrants, and its criminalization of poor people. I got into that anti-Giuliani activist work because I was working at Meow Mix and other queer bars and at the gay bookstore A Different Light, and the other working class queer and trans people I met in those spaces were being affected by and organizing against Giuliani’s policing of night life and sex workers. I was also part of activist work to push back on how the lesbian and gay rights movement was increasingly pushing a conservative pro-military, pro-police, pro-marriage agenda. In 1998 I co-organized, in a group called the Fuck The Mayor Collective, the first Gay Shame event which took place at a queer performance and living space called Dumba and focused on articulating a queer agenda that would be the reverse of what we saw at corporate pride. For this event, we made a zine called Swallow Your Pride, also focused on building an anti-racist, anti-capitalist, feminist queer and trans resistance to the mainstreaming gay politics. This stuff feels like ancient history now, since that mainstreamed gay agenda is so ultra visible now and embraced by the US government and a lot of the 1%.

OP: How did your activism change as a result? DS: The kinds of responses I got from people who had experienced similar police harassment and bathroom issues and problems trying to get legal help spurred me to start the Sylvia Rivera Law Project. I could see that there was a huge need–trans people were and are targets of legal systems that enforce rigid gender norms, especially on poor people and people of color. And I could also see that there was building momentum for racial and economic justice centered trans resistance. I started the Sylvia Rivera Law Project as a space for both these things. I started it with a grant to be one lawyer providing legal help, but immediately we put together a steering committee to create a collective structure that could capture the energy of the community and work to provide more help than we would ever be funded to provide given how invisible and unpopular trans issues were at the time. SRLP is now 14 years old, still providing free legal help to trans people facing violence in prisons, foster care, public schools, psychiatric hospitals, immigration proceedings and more.

OP: What was the climate of understanding around trans people back then as opposed to now? DS: Trans issues are more visible now–a mainstreaming process is under way where certain trans lives are more visible in particular ways, and we are seeing a lot of backlash because of that. From the perspective of the people who come to SRLP for services, though, things are not getting much better. Providing actual help to trans people in need is still not popular with funders so the work is still always on a shoe-string, always with a waiting list of people who need services, and the conditions facing trans people in need are worsening. The immigration system, policing and prison systems have grown significantly since the project was founded, poor people are poorer, and benefits systems have been cut. Probably more people in the US would now say they know about trans issues or don’t hate trans people because they are seeing more media representations of trans people, but I think we have to really question what that mainstreaming changes. Mainstreamed media representations tend to show us what a “good” or “deserving” person from a marginalized group is and tell us to have sympathy for them. They don’t tend to disrupt narratives about who is “bad” and “undeserving.” So maybe some people who oppose the terrible bathroom bills would say that it is bad if a white, masculine, middle class trans man can’t use a bathroom, but do they feel the same about a disabled trans woman of color with a criminal record? I think a lot of the acceptance that happens when images of “deserving” trans people circulate is very conditional and rarely actually changes what the most vulnerable trans people are going through. My life as a white trans professor might get better, or I might experience some new acceptance because of the mainstreaming, but conditions are still horrific and getting worse for SRLP’s clients who are locked up or who experience ongoing police profiling and harassment, exclusion from jobs, education and health care, and possibly increased vulnerability because they are the ones who will get caught up in the backlash.

OP: What are you working on now? DS: One thing I have been working on lately is trying to get more of the critical ideas I care about into circulation in more accessible ways. I want more people to have tools for thinking and talking about the limits of mainstreaming, the problems with a pro-police, pro-military LGBT politics, the reasons that queer and trans liberation means getting rid of borders, prisons, police, and poverty. I have been making videos and GIFs that I am hoping can circulate more than the writing I have mostly done in the past. In 2015, I finished an hour-long documentary called Pinkwashing Exposed: Seattle Fights Back (online for free) that tells the story of local activists resisting pinkwashing. The goal is to help broader audiences understand what pinkwashing is. I have also been making a bunch of short videos with Hope Dector at the Barnard Center for Research on Women. One series of short videos, called “Queer Dreams and Nonprofit Blues: Understanding the Nonprofit Industrial Complex” is about how the lesbian and gay rights agenda got so narrow and what is wrong with that and how we might imagine alternatives. Another series is about why increasing criminal penalties and policing is not the answer to the problem of violence against women and LGBT people (you can watch these at deanspade.net). For Pride 2016 we released a video called “Queer Liberation: No Prisons, No Borders” that connects queer anti-deportation and queer prison abolition work. We also released some cute GIFs about getting police out of Pride celebrations. Right now there are so many ways that cops, the military and corporations are making themselves out to be “LGBT friendly” as a PR stunt. Its important to meet that queer and trans people and our allies see through this and understand why our liberation is about dismantling these institutions, not being claimed by them.

OP: What is the best thing that has ever happened to you in a bathroom? DS:Generally, sex and drugs, of course. Specifically, a wonderful memory is from some time in the late 1990’s or early 2000’s when the San Francisco MOMA hosted a dance party in the museum. My friends and I were on ecstasy and I remember the bathrooms there were huge, maybe 10 sinks in a line, and we had so much fun hanging out in the bathroom with all the other people on drugs, going between the bright lights of the bathroom and the dark dance floor lighting, washing our hands over and over because it felt good. Perhaps it was particularly exciting because we were used to gay bars and clubs with small, dark bathrooms? I don’t know but I remember the bathrooms being the best part of that party.

OP: What is the most heartening thing you have witnessed in regards to progress being made for trans people in bathrooms? DS: I think, overall, it is heartening that there are so many more people working on this than there were in 2002. Also, it feels like there are just more trans people and I love that. I think the key thing for us now is to think carefully about what we want our movement to look like. Are we fighting to just have a privileged few of us take our places in the existing racist institutions of the US, or are we part of a broader struggle that would actually benefit all trans people and everyone who is harmed by the enforcement of gender norms? One way this comes up is about the bathroom and sex-segregated facilities. We need to make sure the conversation is not just about the bathroom, but that we take that conversation and use it as a way to talk about how trans people are experiencing violence in all the places where gender norms are enforced through sex segregation, especially prisons, jails, immigration facilities, psychiatric hospitals, group homes, and shelters. The most vulnerable trans people facing the most violence are in these spaces, and if we stick to only thinking about bathrooms and/or mainly imagining the ability of white trans people to access bathrooms at school and work, we will miss the chance to intervene on the most significant sites of violence in trans lives.

Radio, Buzz and Stopping Jail from Being Built!

KPFA did some great programming around Pride this year focusing on critical queer and trans political resistance and critiques of same-sex marriage, gay military service and other hallmarks of wealthy white gay politics. Here is a whole day of programs that aired on Pride Sunday. Here is a show focusing on the critique of same-sex marriage advocacy, including Kenyon Farrow, Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore and me. In other news, Buzzfeed published a list of 24 Americans Who Changed the Way We Think About Transgender Rights. I’m excited to be on any list with Sylvia, Marsha, Miss Major, Lou and all these other amazing people.

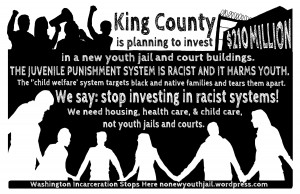

Finally, I am so excited by all the inspiring work being done by Washington Incarceration Stops Here. We are doing an awesome postcard campaign about what people think our county really needs rather than a new youth jail and family court buildings. And we’re building a coalition of groups who have signed on to our Points of Unity. If your organization wants to sign on, no matter where you are, please let us know! We’re also starting a zine so please let us know if you have art or writing you’d like to contribute or if you can help spread the word to people who may want to contribute, especially youth and people impacted by criminalization and child welfare systems.

New Writing in the Seattle Journal for Social Justice

The Seattle Journal for Social Justice just published a new issue that includes a cluster of articles and art on trans issues. You can read the introduction I wrote for the cluster here.

The Seattle Journal for Social Justice just published a new issue that includes a cluster of articles and art on trans issues. You can read the introduction I wrote for the cluster here.

Here is an interview with advocates working on Medicaid access for trans people in three states.

Here is an article by my colleagues at SRLP about the role of lawyers in trans resistance.

Read all articles in the issue here.

We’re having a symposium featuring several articles from the cluster at Seattle University School of Law on October 20 from lunchtime until evening open to the public and free. Please come!

Two Special Issues of Sexuality Research and Social Policy: Journal of NSRC

Paisley Currah and I co-edited the two-part special issue “The State We’re In: Locations of Coercion and Resistance in Trans Policy” in Sexuality Research and Social Policy: Journal of NSRC Vol. 4. No. 4 (December 2007) and Vol. 5, No. 1 (March 2008).

Read the introduction to the first volume here and read the introduction to the second volume here. A table of contents for both issues and links to most of the articles are below.

Part 1 (December 2007): Table of Contents

Introduction to Special Issue The State We’re In: Locations of Coercion and Resistance in Trans Policy, Part 1, Paisley Currah and Dean Spade

Unraveling Injustice: Race and Class Impact of Medicaid Exclusions of Transition-Related Health Care for Transgender People, Pooja S. Gehi and Gabriel Arkles

Sex Workers, Fem Queens, and Cross-Dressers: Differential Marginalizations and HIV Vulnerabilities Among Three Ethnocultural Male-to-Female Transgender Communities in New York City, Sel Julian Hwahng and Larry Nuttbrock

Seeking Refuge Under the Umbrella: Inclusion, Exclusion, and Organizing Within the Category Transgender, Megan Davidson

Transgender Health Benefits: Collateral Damage in the Resolution of the National Health Care Financing Dilemma, R. Nick Gorton

Momentum: A Photo Essay of the Transgender Community in the United States Over 30 Years, 1978–2007, Mariette Pathy Allen

Part 2 (March 2008): Table of Contents

Introduction to Special Issue The State We’re In: Locations of Coercion and Resistance in Trans Policy, Part 2, Dean Spade and Paisley Currah

Talking, Gawking, or Getting It Done: Provider Trainings to Increase Cultural and Clinical Competence for Transgender and Gender-Nonconforming Patients and Clients, Christoph Hanssmann, Darius Morrison, and Ellery Russian

Gender Identity and Hate Crimes: Violence Against Transgender People in Los Angeles County, Rebecca L. Stotzer

The Nonprofit Industrial Complex and Trans Resistance, Rickke Mananzala and Dean Spade

And by the Way, Do You Know He Thinks He’s a Girl? The Failures of Law, Policy, and Legal Representation for Transgender Youth in Juvenile Delinquency Courts, Jody Marksamer

Undeserving Addicts: SSI/SSD and the Penalties of Poverty

I wrote “Undeserving Addicts: SSI/SSD and the Penalties of Poverty” in Howard Scroll: The Social Justice Law Review in 2001. You can read it here.

Abstract

Since the late 1980’s, American media and politicians have produced and participated in a moral panic around the issue of illegal drug use. This panic has generated vivid pictures in the American imagination of drug users as a morally depraved, irresponsible, and willfully criminal underclass. Such images have fueled the “war on drugs,” a multi-faceted rhetoric and policy approach to drug use that focuses on incarceration, interdiction, and other criminal justice strategies. The punitive approach of the war on drugs has bled into poverty and disability policy with alarming persistence. The trend has influenced numerous poverty alleviation and disability programs and protections, leaving drug users increasingly isolated and unaided. This comment explores the impact of such changes on the Americans with Disabilities Act 2 (ADA) and two social security policies, Supplemental Security Income (SSI) and Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI). It questions the wisdom of a punitive response to drug use by examining the alternative model of harm reduction and applying the principles of harm reduction analysis to the exclusion of drug users from poverty alleviation and disability programs. Part I describes recent changes in disability policy, which reflect a decrease in coverage for persons disabled by drug use. Part II describes the context in which these changes occurred, with the war on drugs in full force, and offers critiques of drug war strategy. Part 1I describes the harm reduction model as an alternative to the drug war approach. Part IV examines the impact of drug war policy on the poor, arguing that pushing drug users further into poverty by denying them public assistance will increase drug-related harms. Furthermore, this section suggests that strong social welfare systems can operate to reduce the intersecting harms of poverty and drug use.